Historical background

of epilepsy

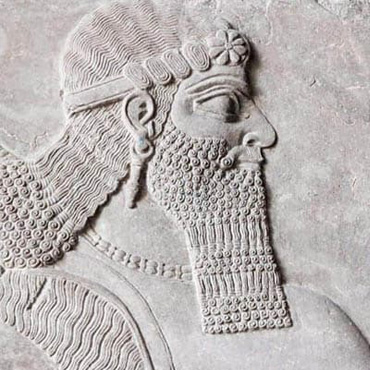

The Sacred Disease, or epilepsy, as it is called today is as old as man himself. As early as 2080 BC, Hammurabi, King of Babylon, made mention of it in his laws. Then, as now, it assumed both medical and social importance.

The laws demonstrated that the prejudice existed, even then, against the person with epilepsy. For example, two of the sections of the “Code of Hammurabi” curtailed the rights of people with epilepsy in what we would describe today as basic human rights. A person with epilepsy was not allowed to marry and could not act either as a member of a jury or as a witness in a court of law.

In approximately 400 BC in the Hippocratic collection of medical writing on the Sacred Disease an alternative explanation to superstitions associated with epilepsy is given. The explanation given is that epilepsy is caused by an excess of phlegm. However, superstition remained and many strange customs evolved.